Limpopo National Park is one of Africa’s most remarkable wilderness areas. It is made up of over a million hectares of vast landscapes. Officially declared a national park in 2001 by the Mozambique government, the park had a long way to go in being established after the country’s protracted civil war resulted in the decimation of 90% of its wildlife population.

The following year Peace Parks Foundation was appointed by the Mozambique Government to assist with the process of developing the park and became the implementing agent for the financial support from the German Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development through KfW. A joint project implementation unit was established and the team, comprising experts from the Mozambique Government and Peace Parks, focused on creating a national park and restoring it to its natural state that would secure a sustainable future.

One of the very first daunting tasks was to demine an area of this vast scale and after that put in place a basic road network and park management infrastructure. Since there was no wildlife, just over 5 000 animals were also introduced (which is only about 5% the carrying capacity of this park) as founder populations.

In 2008, the world experienced a rapid increase in wildlife crime, which, if left to run its course would have resulted in the extinction of several critically important species, such as rhino and elephant, unbalanced ecosystems and southern Africa’s biodiversity in utter chaos. The economic effects, due to the loss of tourism income, would have been far-reaching, impacting most significantly on those living in extreme poverty. In Mozambique, 20% of the park’s revenues is shared with the surrounding communities. These communities also depend on the park for employment and other livelihood opportunities.

Wildlife population numbers plummeted in the wake of the world’s insatiable demand for rhino horn, ivory, lion bones, leopard furs or pangolin scales. Limpopo National Park’s fledgeling animal population came under even more pressure and with its proximity to the wildlife-rich Kruger National Park, it became a gateway used by wildlife criminals who would move through the park to hunt in Kruger. This meant that rangers had to not only protect their own park’s animals, but also those of their neighbour. This not only threatened the lives of rangers, poachers and wildlife but also had a negative impact on the promotion and expansion of the transfrontier conservation area concept, specifically the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park which includes Limpopo, Kruger and Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park.

“We estimate that by the end of 2015, elephant poaching had peaked with the annual loss of about 30 to 40 animals in that year,” says Peace Park’s Peter Leitner, stationed in Limpopo National Park. It became clear very quickly that security teams needed to increase their effectiveness if they wanted to stand against the severe onslaught.

Not on their watch

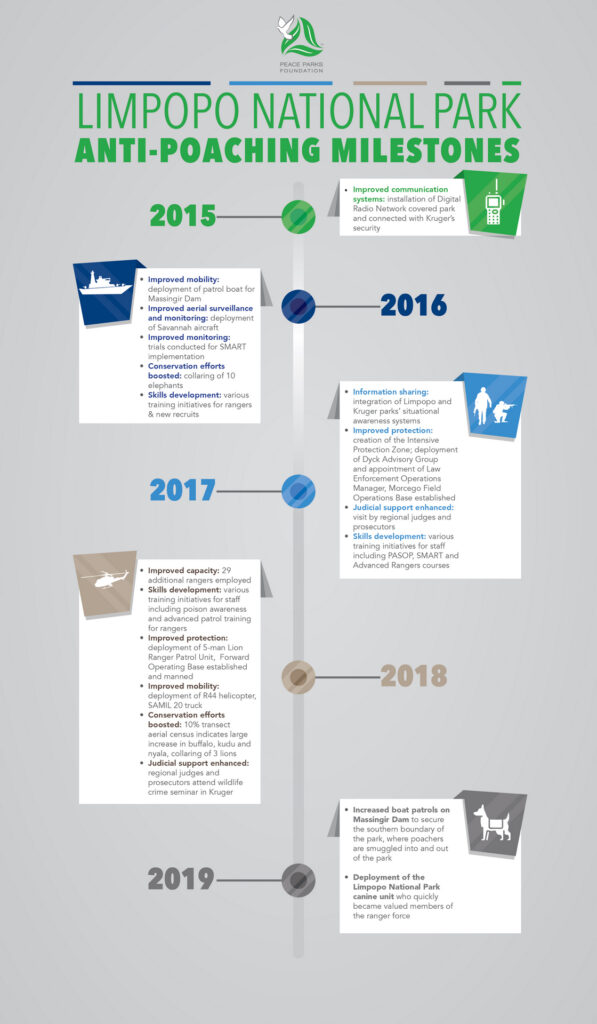

The first step was to establish a communication system that would cover the entire park, allowing rangers to be in constant contact with each other and the park’s headquarters. Peter says, “This greatly improved our ability to respond to emergency situations and execute effective operations. It also reduced risks, such as teams accidentally firing at their own staff in dense bush, delayed reactions to incursions and miscommunication, which hampered the anti-poaching efforts. A digital radio system was subsequently installed that greatly improved not only internal park communications, but also integrated with Kruger’s radio network, allowing for real-time cross-border information-sharing, and consequently synchronised response and pursuit, between ranger forces.”

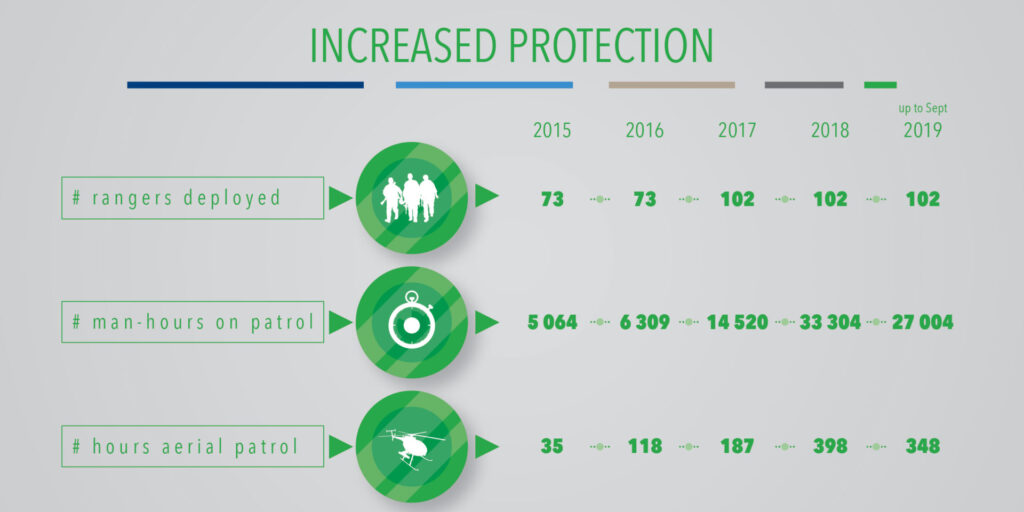

Over the following three years the Limpopo National Park ranger force benefitted from a range of interventions, which included various forms of skills and refresher training, as well as the employment of 29 additional rangers, improved aerial capabilities with the deployment of a Savannah aircraft and a R44 helicopter, and the installation of software which allowed for real-time tracking of security assets, data-collection and information-sharing. Patrolling efforts also greatly improved with 2 574 patrols undertaken in 2018, up from only 633 in 2015.

It was in this year that the anti-poaching strategy was revised with the creation of an intensive protection zone. “We decided that in order to be more effective we had to focus 80% of our resources on 20% of the park where most of the remaining wildlife could be found and also had the most potential for tourism,” says Peace Parks Senior Project Manager, Antony Alexander.

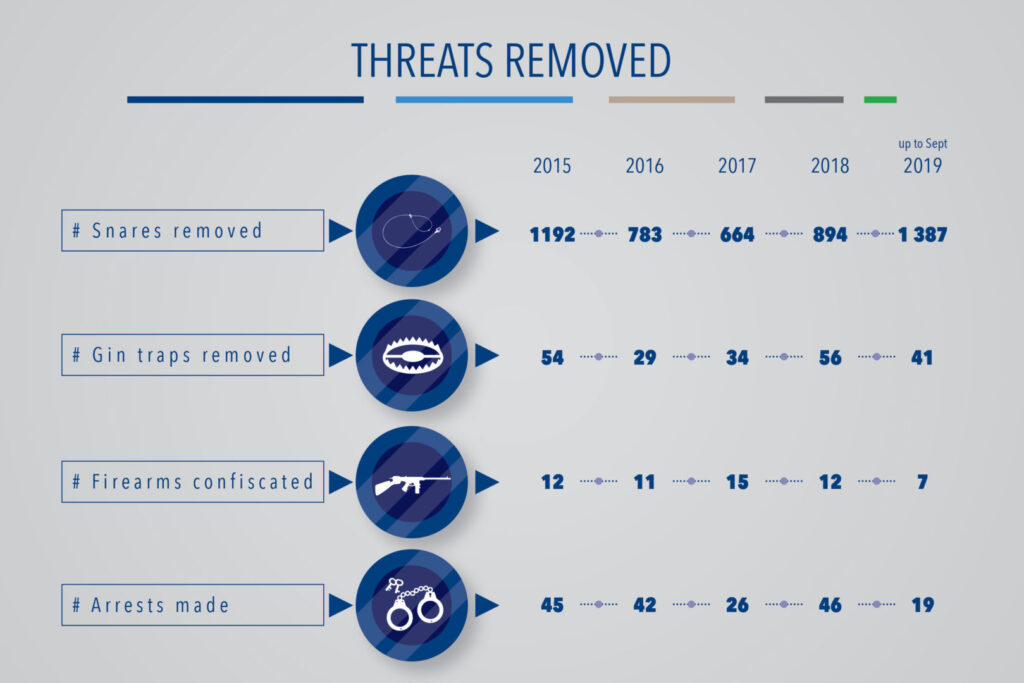

The intensive protection zone now lies adjacent to the Kruger National Park border to where it serves as a security buffer preventing poachers from entering South Africa. Its establishment had an immediate and direct effect on anti-poaching operations as the increased number of rangers on patrol resulted in almost 900 snares recovered and 46 arrests – 20 more than the previous year. Increased aerial surveillance also had a psychological effect on poachers, deterring them from attempting illegal activities in the area.

Enhanced operational support

Building on the successes of the new anti-poaching strategy, Mozambique’s National Administration for Conservation Areas (ANAC) signed an agreement with the Environment Management and Conservation Trust (EMCT) enabling them to bring to the table a range of tactical expertise that would strengthen anti-poaching efforts and increase the safety of security operations for those on the ground.

Two field operating bases were established where, under the command of the Mozambican authorities, rangers are supported and trained by personnel from both EMCT and Peace Parks. These locations also provided teams with much-needed infrastructure and technologies from which to better plan and execute patrols, as well as respond to potential poaching incidents.

“With the higher patrolling efforts and improved daily collaboration between Kruger and Limpopo national parks’ staff, a marked decline in poacher incursions was reported by Kruger. Over same period January to November this year, compared to 2018, we have seen incursions reduced by 63% in two most active regions in Kruger adjacent to Limpopo National Park,” says Peter Leitner, Peace Parks Foundation Project Manager in Limpopo National Park. It also had a direct and immediate impact on the number of elephant killed in Kruger, which has reduced from 79 in 2018 to 29 as the end of October 2019.

Intensive Protection Zone Regional Ranger, Samual Chauque, comments on improved operations. He says, “I have been a ranger in Limpopo National Park for 15 years. Since the beginning until now I have seen a big improvement. Now, if we get in contact with poachers, we can call a helicopter to come and help us. Within ten minutes the helicopter is there, they can see us on the ground, do a procedure and we can easily catch the poacher.”

Wildlife populations growing

An aerial census published by ANAC in 2019 indicated that several wildlife species’ populations are doing very well in Limpopo National Park. For example, since 2014, census results indicate that buffalo numbers have increased from 1 339 in 2016 to 5 883 in 2018. “Continued growth in numbers of indicator species such as nyala and kudu, which are evenly distributed across the Park, as well as the high growth in buffalo numbers indicate a healthy and widely protected ecosystem,” says Antony.

The census did, however, indicate that elephant populations had decreased, Peter explains, “in contrast, the decrease in elephant numbers indicates that there remains pressure on higher valued species. As aerial and foot patrols and intelligence have indicated that less than ten elephant have been poached per annum over the past years, this population change is considered primarily due to the movement of elephant within the open system with Kruger National Park where there is plenty of water during the dry periods. They also feel less threatened due to the proximity of community villages in and around the Limpopo National Park. We have seen that through the resettlement programme, areas are being quickly re-inhabited and elephants are now regularly seen around the Park headquarters at Massingir Gate.”

Over the last two years, Limpopo’s park management team has embarked on building relationships with those tasked with prosecuting wildlife criminals caught in the act of wildlife crime. In 2017, regional judges and prosecutors visited the park to get first-hand knowledge of the processes involved in securing the park, as well as the impact of wildlife crime. This was further boosted by a wildlife crime workshop held in 2018, during which regional judges and prosecutors visited Kruger National Park. Since then, the number of successful prosecutions increased and harsher sentences were handed down. Notably, a Mozambican court handed down sentences of 17 and 19 years respectively to two Mozambican citizens who killed two rhino in Limpopo National Park in August 2018.

What the future holds

With protection efforts securing the park’s natural resources, Peace Parks Foundation and ANAC are also focused on the communities in and adjacent to the park. One of the ways in which the park aims to assist is by implementing agricultural projects and providing water through irrigation schemes. So far, 18 irrigation schemes have been launched that provide food security by minimising rain dependency, offer health benefits as farmers can grow different types of crops resulting in a varied diet, as well as improved income through the sale of excess produce. These projects also involve teaching community farmers to make use of climate-smart conservation agriculture techniques that limit the impact of agricultural activities on the natural environment.

Educational programmes are also implemented which focus on equipping young people with the knowledge and understanding of the impacts of unsustainable natural resource use.

Cornelio Miguel, who works as ANAC’s Transfrontier Conservation Area Coordinator, says “The Government of Mozambique has prioritised the transparent conservation of natural resources as one of the pillars that need to be looked at. We have almost one-quarter of the country as protected and conservation areas, which makes them very important features of the country. We see them as areas to where, in future, people will go for leisure to rest and to interact with wildlife, intact forests and wildness. We also see the park benefitting the communities in 10 to 15 years. Once everything is well established, I would like to see Limpopo National Park serving the nation and also humanity.”

The vision of Peace Parks Foundation is to re-establish, renew and preserve large functioning wilderness areas that transcend man-made boundaries in order to protect the ecosystems within them, ultimately securing the animals that move within its wildlife corridors.

The efforts by ANAC and Peace Parks have been synergised with and supported by the German Government through KfW, the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and BioFund whose funding support have been instrumental to the development of Limpopo National Park.

“But what does it [the protection of wildlife and the development of conservation areas] mean at the end of the day for the local population? Is it a better land use than what was previously done? We are absolutely convinced that it is. We see the livelihood improvements of the people in the area, where there is an investment in agriculture, not having to depend on the rainfall but being able to draw from the water sources available to grow crops throughout the year. And then employment. Tourism employs a great many people, on average three staff members per bed, so it provides all these other opportunities, which broadens the economic base for the region.”

Peter Leitner, Peace Parks Foundation Project Manager